Sunita Prasad

Still from Visits 2021. Video. 14:12

Visits

An interview with Sunita Prasad by Rah

Sunita Prasad is a New York City based artist working in film, video, and performance. Her works often employ methods of hybridization between documentary and fiction. Sunita’s projects span a variety of subjects, landing frequently on gender, representation, and social movements. Here she reflects on the more personal history explored in Visits, her video with Temp. Files, and the interplay of memory, place, friendship, and belonging.

A PDF of the interview is available here.

Rah: Sunita, you have created a multifaceted oeuvre while working in the genres of performance art, drag, video and documentary. How do you navigate new mediums to address the idiosyncrasies of a particular situation or narrative?

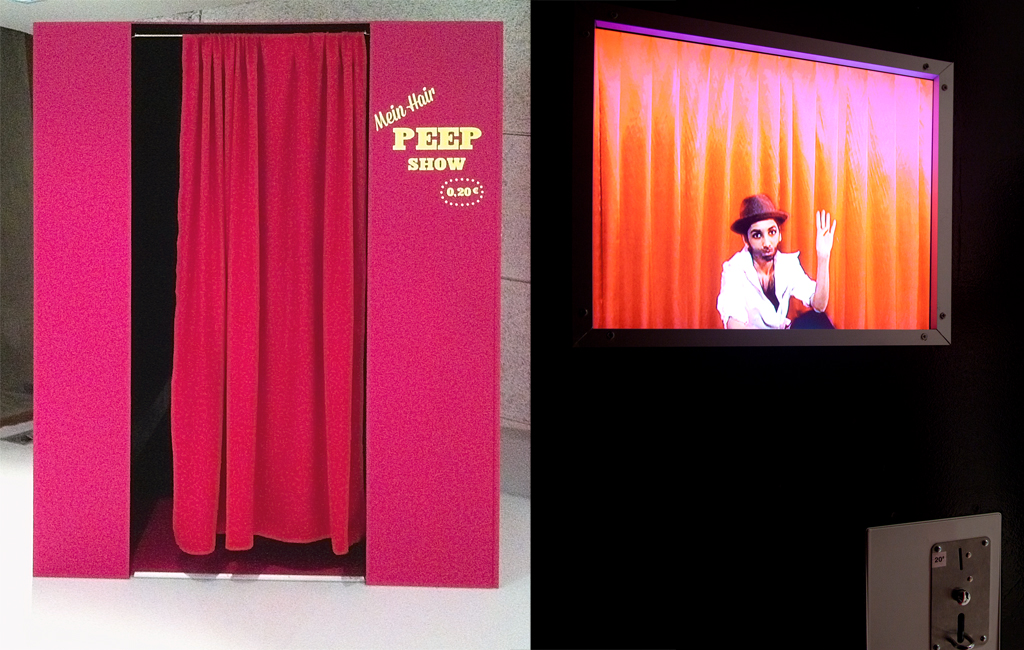

Sunita: Most of my work stays somewhere in a range of time-based work. Whether it's film or video installation, performance, or most recently, dabbling in traditional theater, there's a storytelling element and there is an element of time in all of it. The aesthetics can change a lot based on what the exploration is, though. For example, when I was doing a research-based performance that had to do with the sale of images of one's body on the internet, I decided to harken back to an earlier technology. In order to highlight the transaction, I made a coin operated video booth, so the viewer had to actually perform the act of paying to see the art work. Another time, I collaborated with a glassblower named Liesl Schubel to make custom screens that had more organic “pregnant body” forms for a video installation about my body and time. So the format tends to follow the subject pretty often.

Sunita Prasad, Mein Hair, installation view, 2011

The idea for this video, Visits, grew out of a 20 year friendship I’ve had with writer and actor Jess Barbagallo. Twenty years is a long time, but we’ve always known it could have been longer. Jess and I both grew up in the Syracuse area and were both teenagers exploring our queer identity in the late 1990s. Remarkably –considering how tiny the Syracuse queer youth scene was at the time– we never met. I asked Jess to go on a trip home with me to show each other the sites that were important to each of us during that time. I’m extremely grateful that he agreed and we got to make this together!

Rah: Visits is an intimate recollection of the many spaces and institutions that have shaped you and Jess’s experiences as Queer subjects. Members of the LGBTQ+ community seek spaces that are safe for queer expression. These sites are often vital to the community’s or individual’s survival. Why did you select these spaces to revisit in your video?

Sunita: There was a healing aspect to traveling through the city and surrounding towns with Jess. I have always been so negative about Syracuse, and about my queer experience in Syracuse in particular. Growing up, I thought of it as a place of stagnancy and bigotry and depression. For Jess to reframe the late 90s upstate experience and say that the isolation we felt holds possibilities of intimacy and connection was illuminating for me. He grew up further out from the center of Syracuse, in the farmland and in quieter towns. I loved his description of how wild it is and all the places there are to hide.

Rah: In your works which are often character-driven, you reference queer history and a culture of drag performance. How are you queering the genre of documentary? Are there any strategies or techniques that you’re using to subvert or challenge queer represenation in this particular medium?

Sunita: I wish I could say I have consciously tried to queer any genres. I haven’t, but queerness is visibly embedded in what I make. There are queer characters, challenges to the binary view of gender, or challenges to normativity more broadly in all of my works. The reasons for this aren’t mission-driven so much as born of the fact that I was forged in a queer community (Thank my stars! Such radical love and friendship I’ve known!) and that is the perspective from which I continue to see.

Sunita Prasad, still from Presumptuous, ongoing.