Rachel Stevens, Coordinate Meterology Systems. 2021. Still from Video. 07:36

Rachel Stevens, Coordinate Meterology Systems. 2021. Still from Video. 07:36CMS:

An interview with Rachel Stevens on the circuitousness of interdisciplinary practice, managing an analytical mind, and the freedom of being data.

Rachel Stevens is a NYC-based artist and researcher interested in social ecologies, critical geography and experimental media. She has exhibited her work and participated in residencies around the world. Rachel typically explores pressing sociopolitical and ecological issues through her art practice. For Temp. Files she shifted gears to pick up a personal project that she began more than 20 years ago.

A PDF of the interview is available here.

Kara: In your bio it says you are interested in “ecologies and geographies, moving images and archives.” It’s interesting to think about moving images as ecologies or geographies or archives, or thinking of geographies as moving images or archives, and so on. Do you think of the similarities as well, or are they distinct interests?

Rachel: Hmmm. I am a very interdisciplinary person, and it is really hard for me to come up with an elevator pitch. I was trying to name all of my interests and different parts of what I do, so they're kind of different, but, of course, interrelated.

There are fields called media ecology and critical geography and social ecology. I'm into all those things. In the Spatial Narratives class I teach at Hunter College, we read some of Keller Easterling’s Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. She describes how the world is organized through infrastructures and technologies—such as the thickness of credit cards or the height of loading docks—that are designed to allow for the smooth flow of capital. Henri Lefebvre says that we construct space (socially, politically), and then space constructs us. Media – video, is made up of data now. So there's a more fluid relationship between media, the kinds of data that structure our environments and behaviors we are encouraged to have.

Over the past few years, my work has been concerned with ecology and place, particularly bodies of water in and around New York City. My friend Lize Mogel’s work on radical cartography, and now water infrastructure, and Trevor Paglen’s early work and ideas on experimental geography really inspired me to think about space and place. But I’m also terribly interested in experimental documentary and interdisciplinary moving image art. I also have a long-standing kind of virgo + scorpio fascination with archives. While studying photography in art school I ended up making sculpture. I can’t keep a straight line.

Kara: Do you want to talk a bit about the history of this project?

Rachel: The media in this video comes from my MFA thesis project at UC San Diego. I had been making sculpture installation and working with digital media and thinking about the relationship between the two – about materiality and immateriality, about translation into data and the abstraction of form and content that needs to take place in order to make something virtual or to send it through a network.

I had a strange epiphany while playing the Sony PlayStation Game Tomb Raider for the class while I was a TA for Lev Manovich, and that experience was the kernel that became my thesis. In addition to an interview with Lynne Dewart and a 16mm film documenting her measuring my whole body for a dressmaker’s pattern, the installation included sculptural landscape elements made out of plywood, a 16mm film loop of Lara Croft swimming underwater, two video projections, four audio soundtracks and a painting made of an underwater image in the game that was a glitch with no characters in it and the body pattern. The audio soundtracks included an interview with an AI vision researcher and someone singing the song Laura karaoke-style with a band at The Red Fox Room in San Diego.

Laura: experiments in immersion and identification (1999)

Laura: experiments in immersion and identification (1999)Kara: What aspect of it called you to pick it back up again? And what has changed since you started this project 20 years ago?

Rachel: The project felt unresolved. At the time I thought maybe it should be video rather than an installation, so I could make all the associations and references and integrate the different parts, but I didn’t know very well how to make video. So now is my chance!

The connecting threads between artists in the Temp. Files group seemed to be working with performance, and thinking about relationships to personas, technology, gender, and language. So this material came to mind right away when I thought about what to work on.

I am super excited to work with video as a language since you can include so many different elements into one work: images, writing, sound design, the temporal, photography, found media. Not to be too gendered in my references, but the video artist, Pippilotti Rist, talked about video as being like a woman’s handbag that you could toss everything into and Ursula LeGuin wrote an essay called “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” that privileges gathering over hunting. Of course then the challenge is to make some kind of order or structure with the elements that you toss together so that it is legible to the viewer.

These days, during the pandemic, everyone is on Zoom. Younger people are on TikTok, or on their phone communicating remotely, or in a game world. This relationship between you and your “virtual self” is very fluid and normalized, an extension of who you are in an everyday way. So that's really changed.

Kara: I love the complexity and density of the juxtapositions you are making in this video. Can you describe each component and how you found the structure to hold it all together?

Rachel: Translating the parts of the original installation, which was hard enough to contain, into a linear video that incorporates enough of the threads was really challenging. It was also hard for me to bring myself back into the conceptual world of the project, made by a self from the past. I was exploring women and technology and the body in a way that I feared was sometimes regressive. People in the Temp. Files group pushed for some version of me from the present to be in the film, which I resisted, but it is necessary, I think. It doesn't seem to make sense if I don't have my present self as the third part of it.

Lynn Dewart, the interviewee, is a catalyst. First of all, she was able to make the dressmaker’s pattern of my body, but I just love that she is such a fluid person. She's an engineer. And she's also an artist, so she understood that kind of creative impulse, like, why would I want her to make a dress maker’s pattern of my whole body? And after working as an engineer she chose work that's very material – sewing, making costumes – which is about performance and about other women. So she could stand on her own in the video, but then I also have the 16mm footage of the measuring. And how do I explain the relationship of everything to Lara Croft and Tomb Raider and also bring in sculptural elements from the installation?

People in our group imagined a two-channel installation, so I was like, okay, I'm just going to go with a two-channel structure, something I can accomplish in the timeframe, even though it feels reductive, a binary system. Maybe the piece won’t do some of the other things on my mind, but that's the process of making work, right? Committing to a form, to one version. I was able to work through the relationships and also had to let go of control a bit.

Kara: Can you talk a bit more about Pippilotti Rist’s handbag and Ursula Leguin’s gathering over hunting?

Rachel: When I was in high school, my main art form was collage. Just cutting things out of magazines and reassembling them and making associations between the images. When I went to art school in the late 80s, I had to beat that impulse out of me. The art world at the time was conceptual and, you know, it was the time of postmodern theory. Somehow I had to resist the collage impulse.

Kara: Ha! I felt like I had to do that when I went to graduate school too because collage is too precious and haphazard, decidedly not conceptual.

Rachel: And unskilled and intuitive. But my mind works in a really associative way. Harun Farocki uses the term “soft montage” where you bring two images together, but not like A/B, as in montage editing, but A and B in the same space next to each other at the same time. There’s also that famous improv exercise where each person begins their response by saying “yes, and” rather than “yes, but.” I think that might be a technique in couples counseling as well. I think about things that way – holding different ideas together in the same space.

I have a project I'm trying to work on right now – about the St. Lawrence River – and having similar problems, where I'm thinking about it in so many different ways at the same time it's hard to write that main storyline with the narrative arc that they ask for in grant applications for documentary feature funding.

Kara: In this piece you seem to be thinking about digital and analog geographies and how one bleeds or morphs into the other. Is there a distinction to be made between analog and digital or is that a meaningless binary now? Where do bodies fit into this conversion?

Rachel: Since our relationship to the virtual has been so normalized over the years, the topic per se does not hold a lot of interest, but the now archival quality of the media from the Tomb Raider project gives it a different kind of appeal, maybe more ironic. Looking at relationships between the digital/virtual and the material is still important, of course, and I am reminded of the piece by Trevor Paglen in which he photographs the internet cables that run under the ocean that transmit all the data. Or how energy intensive it is to process virtual currencies such as bitcoin. There is no virtual without these material supports.

The original project was a lot about the psychological aspects of being immersed in a virtual environment, identification slippages, and the kind of mechanisms that allow you to do that. Looking back at the work it seems that it's also about the desire to be free of the body. You're so encumbered by the body, and somehow, in this imaginary, to become data is very freeing.

Kara: Is the experience of being Laura Croft still a fascination?

Rachel: I remember the fascination but now, my work is so different. In my past few projects, I've worked more collaboratively and focused more on ecology and place. My friend and collaborator, Meredith Drum, and I made an AR walk and game about oysters, that took place on Governors Island. The history of oysters in NYC is a microcosm of what has been wrong with our approach to the environment but also a lens for looking at rich histories and entanglements of social and economic systems. Then we worked on a project where we interviewed people on the Lower East Side about their seafood recipes and researched ecological safety information and made a book called Fish Stories Community Cookbook. The project was inspired initially by seeing people fishing in the East River, which is very polluted. People eat the fish to survive, to eat or to sell it to support their families. But in general, people living in NYC don't realize that they're living in the middle of this rich estuary.

![]() Fish Stories Community Cookbook (2015, with Meredith Drum)

Fish Stories Community Cookbook (2015, with Meredith Drum)

Kara: This seems like a good segue. I wanted to ask about your St. Lawrence River project. Can you tell us more?

Rachel: The project is called Place of the Big River. After attending a residency that included visits to contested sites for Klamath Modoc in the Pacific Northwest, larger patterns of settler colonialism came into view for me. I thought about the small town that my Dad's from, Massena, NY, which is on the border of Canada on the St. Lawrence River. The town is next door to the Akwesasne Mohawk Territory, which I knew almost nothing about. Since I've become interested in water ecology and infrastructure it made sense to learn more about the area. There's this big power dam, shared between Canada and the US, and then the St. Lawrence Seaway, built in the 60s, that enabled international ships to go all the way to the Great Lakes. My cousin works for Alcoa Aluminum (now also Arconic) nearby. After the power dam was built, GM had a plant there as well. Now there are three Superfund sites on the river. Yeah, there's so much to talk about.

My friend Pawel Wojtasik came with me to Massena and we interviewed Dana Lee Thompson, a Mohawk activist fighting the forces behind the industrial pollution for over 30 years. We got to interview her husband (also an activist), and the head of the environmental division, and a couple of tribal chiefs about the industrial pollution. We also began to learn more about land sovereignty and jurisdiction issues, which are complicated by the US/Canada border. New businesses like cryptocurrency are cropping up, because they have access to cheap power from the power dam. And I want to show issues around invasive species and climate change and nod to more-than-human perspectives. So this small town, that as a kid I experienced as boring and stuck in the 1950s, is an incredibly dynamic, fraught, internationally situated place with huge infrastructure and ecological issues.

Place of the Big River (research project and documentary in progress)

Place of the Big River (research project and documentary in progress)Kara: Wow, what an amazing microcosm.

Rachel: Yeah. And I want to show all the relationships between these things, which is kind of too much for one project (laughs.)

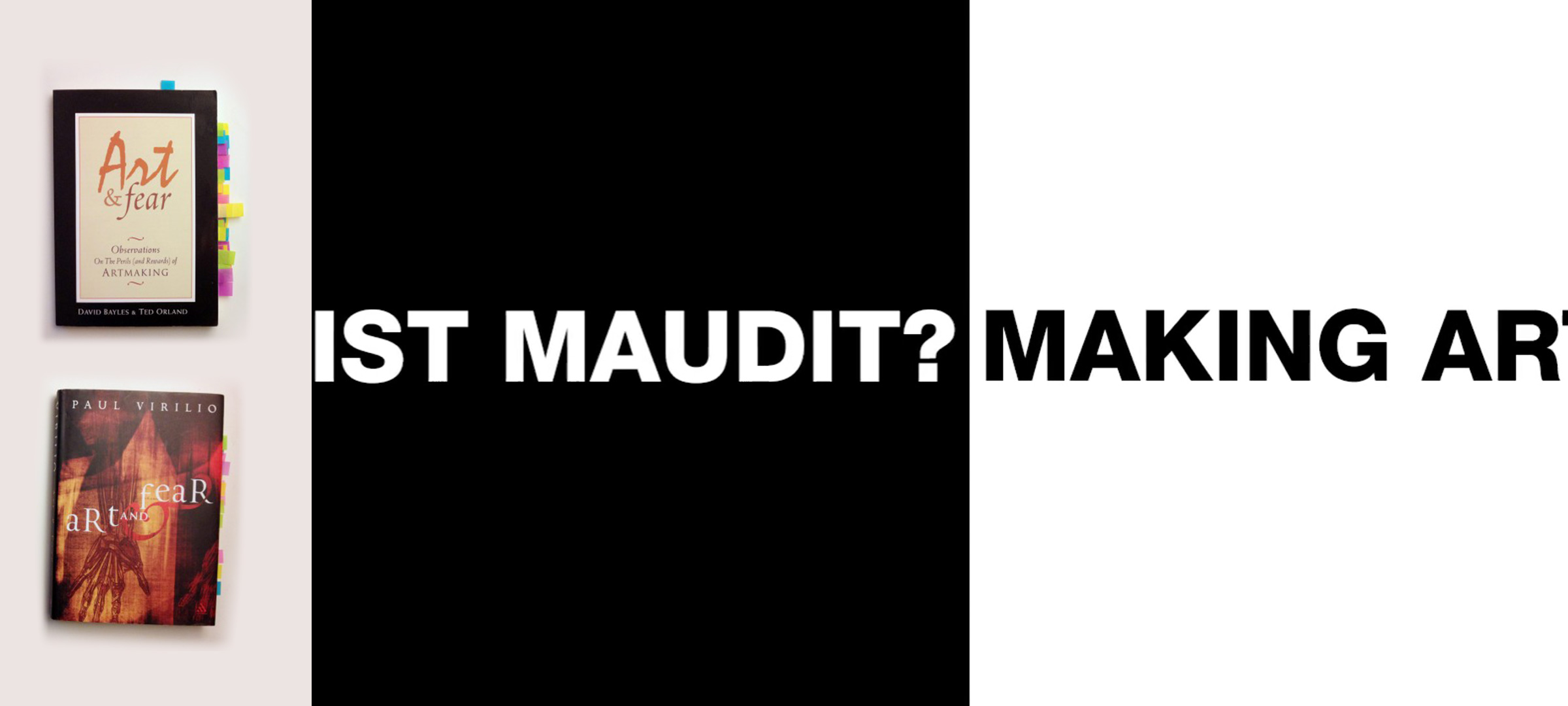

Kara: In one of our meetings you showed us a video called Perfection is the Enemy of the Good where you alternate between text pulled from two very different books both called Art & Fear, one is a self help book for artists and one is a critical theoretical political rant. You said in an email exchange about this that these dueling perspectives – the “intuitive/affective making vs. analytical theorizing seems to be a driver or an impediment” for you. I love the idea of something being both a driver and an impediment. Can you talk more about this?

Rachel: Now that I know your work a little bit I can see why you would notice the project about self help for artists. :-D

I feel like it’s common for people who go to art school, or, at least, like when you and I went to art school, that they make you read all this art theory and texts that are somehow adjacent to art making. I had this professor, who is a sculptor, who saw me reading and said, “Stop reading, it’s bad for you,” while other professors were making you feel like you should be able to discuss Deleuze and Derrida. It feels like a conflict. Sometimes the process of art making – you need to get yourself into this bubble and shut everything else out. Whereas reading and thinking more critically, it's a different kind of bubble, where you're focusing on other people's ideas or language and having to be more accountable or legible in the way that you're thinking. I often don’t feel like I make a lot of headway in either direction, because I'm trying to do both, or to go back and forth. So in the Art & Fear piece, I was making fun of the two poles, which are each kind of hysterical. There's the problem of fear in art making where the solution is to be very gentle with yourself and give yourself positive reinforcement. And, then, the other one, which is to think much more critically, and, in a larger way, about culture and politics, as in the case of Paul Virilio, who here wrote a kind of rant about the 20th century. That inner conflict is somewhat painful, so my approach is to laugh about these two different ways of moving in the world that don't seem compatible.

Perfection is the Enemy of the Good (2014) Video, 6min. View here: https://vimeo.com/88616177

Perfection is the Enemy of the Good (2014) Video, 6min. View here: https://vimeo.com/88616177Kara: And how has it been working through this project as part of Temp. Files with the compressed timeline but also lots of feedback and support?

Rachel: It's been amazing. It's really helpful to have a structure. It's helpful to have specific people to bounce ideas off of, and a context and a timeline. Although I have run into so much internal resistance trying to pull all the parts of this project together, I feel grateful for the pressure of the Temp. Files project and the supportive and insightful input from the others. There is a lot of smarts and experience in that zoom room. The timeline is short, but you don't have time to obsess or rethink things.

March 2021

Fish Stories Community Cookbook (2015, with Meredith Drum)

Fish Stories Community Cookbook (2015, with Meredith Drum)