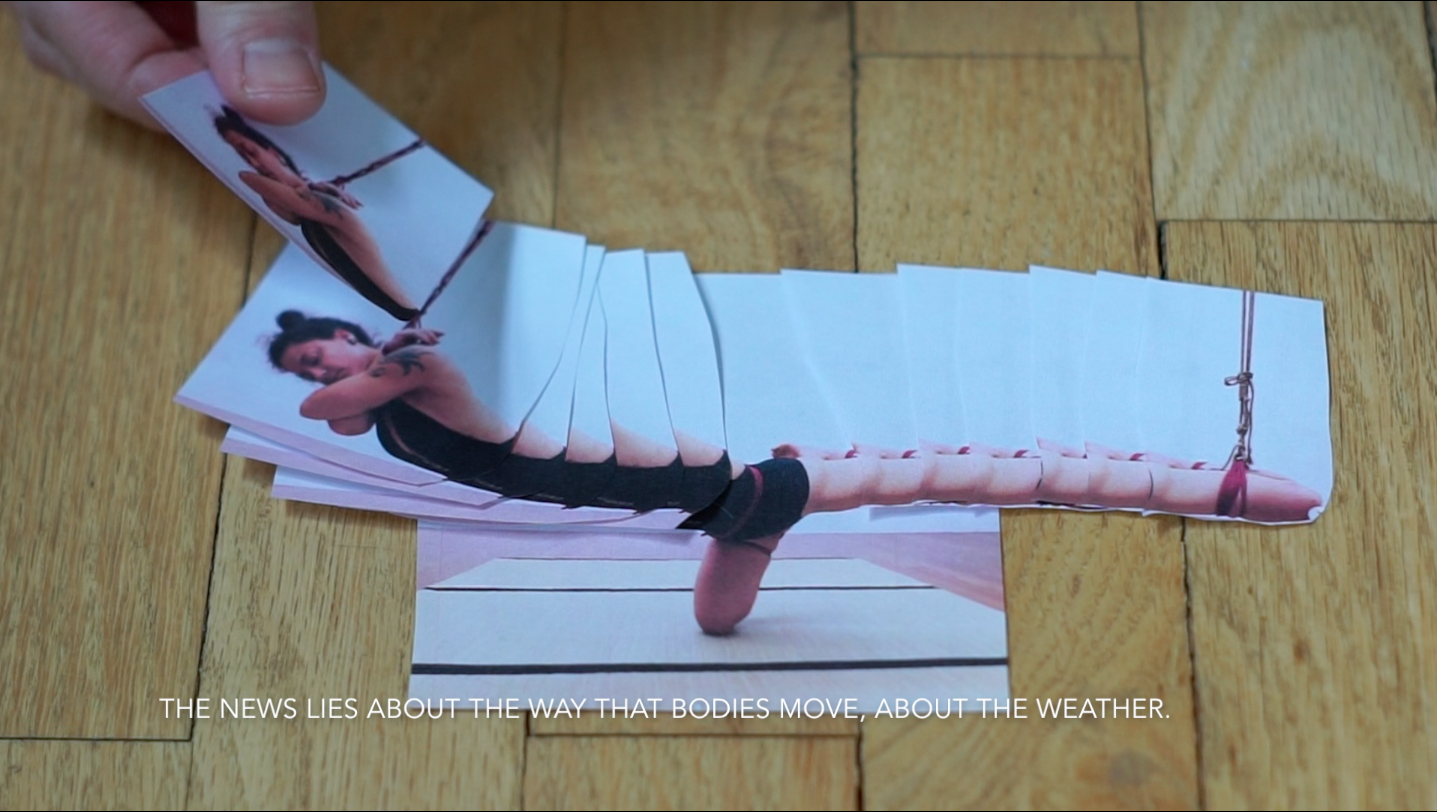

Emily Brandt, Still from Everything outside is replicated within. 2021. Video. 03:32

Embodied Undoing: An interview with Emily Brandt by Sunita Prasad

Emily Brandt is a Brooklyn-based poet of Sicilian, Polish & Ukrainian descent. She is also an educator, co-founding editor of No, Dear, and organizer of the LINEAGE series at Wendy’s Subway. With her casual and gently matter-of-fact air, I imagine her as the kind of teacher who gives assignments that involve collecting all your trash for a week and making art out of it. As an artist, she is prolific, meticulous, and socially engaged. We met recently via video chat to discuss whether plants might be smarter than animals, how to leap the walls between artistic media, and the fine line between meditation and obsession.

A PDF of the interview is available here.

Sunita: I feel a little unqualified to interview you, because I have such glancing involvement with the poetry world.

Emily: That’s wonderful, because that's how I feel about the video world. So we're in the same boat.

Sunita: I’m going to start with the obvious question first: You're a poet. Why the expansion into video art?

Emily: I've always been interested in visual art. As artists we think often in terms of one medium. It's helpful sometimes to take a step back and consider yourself an artist, broadly. The skills that you are really honing in a particular medium are going to transfer to other places, and then those experiences help you deepen in your core medium. I really feel that.

At first, I was having anxiety about making a video. I was using strategies that [Temp. Files co-founder] Tusia was suggesting along the way of how she works. And while some were extremely useful, I was still stumbling. It wasn't working for me because that wasn't my vocabulary. And then I had a conversation with Rico Frederick, who is a poet and a visual artist and designer. I asked him, "How do you approach visual art?" And he said, "This isn't visual art, it's poetry." And I thought: “Yes."

I shifted to think of it as making a poem. That really helped me to think about intersecting images, which in a sense, is a storyboard. It was just a shift of gears to: "I'm making stanzas, that makes sense to my brain." And it translates very much to this other medium.

Sunita: I appreciate what you're saying. Through the process of grant applications that require it and the way the economy of art is set up, artists do kind of silo ourselves into disciplines. But as people, we are much more multidisciplinary naturally.

Emily: Exactly. And one of the ways that artists might stop taking risks is by assigning ourselves to a single discipline. It's powerful to push yourself into other territory and see what happens there. The worst thing that's going to happen is you're going to make something that you're not psyched about.

Sunita: Yeah. Although that can feel like the worst thing that can happen, period.

Emily: It depends on how you sit with it, right? It’s okay. It’s going to help you make the next thing that you are psyched about, right?

"If more space is needed," erasure & collage, 2011

(album cover art for Nature Program)

(album cover art for Nature Program)

Sunita: The domestic space is so deeply invoked in this poem, and yet the theme is largely of external or societal influences on the individual. Is the setting of the home a unit of society, or a refuge from it?

Emily: In the world of this poem, the home, or domestic spaces broadly, are inevitably a unit of society, even when attempting to function as a refuge.

Sunita: One thing that I noticed when I read your poems online is that the text is very visually laid out. And in the video format, we can no longer see the text. So how has that changed the work? Or is that even important to you?

Emily Brandt: That is important to me. There are some poems where that might not feel so essential, but with “Everything outside is replicated within,” I wanted to maintain the line breaks in the video’s subtitles. A lot of the lines are end-stopped to express a tongue-in-cheek confidence, but there is also some enjambment that I wanted to keep visible. Also there's something else that happens when you breathe through a poem, and you vocalize it, that lifts it off the static page. A poem is a nice thing because it lives in these two interrelated universes: embodiment and stasis. In the case of this video, I think some people look, some people listen, some people read, some people do all of that simultaneously, and I’m okay with that.

Sunita: Was it a process to arrive at being okay with that? Or did you go in feeling open to that possibility?

Emily: It was a little bit of a process. I had a strong attachment to the poem in the beginning, because my book Falsehood came out at the start of COVID. I had a multi-city book tour planned and everything obviously got canceled and I had some disappointment around that. Because the poem is the last in that collection, and Temp. Files started close to that time, I initially felt, "Okay, it's going to be a poetry video."

Sunita: What does “poetry video” mean here, that is different from where you arrived?

Emily: Ha, I don’t know that I can authoritatively define that. But I do know that lots of poets make promotional videos for their work, and I didn’t want this to be that.

I had to think beyond that. The poem and the video are working in the same direction, but it's not really about the specific poem as much as it is about this process of considering how we collectively examine and undo socio-political conditioning.

This poem had a lot of visual possibilities. I didn't want to literally represent what is being said in the poem, but I did feel that I could follow the flow of interconnected images that are akin to the objects and events in the poem. I was thinking a lot about the process of infusion, as with literal tisanes, and as it happens internally, being in a given society. Tea is referenced in the poem, which calls in both a long legacy of brutal colonialism, as well as a reverence for the efficacy of plant medicines. The processes of infusion are very clear to me. What is less clear is the possibilities for selectively reversing or undoing that.

I started with the sound before I made the visuals. I wanted the sound of my voice to be literally infused through a kettle to see how that would work out. After creating that effect, I became interested in what kinds of images would also consider possibilities for processes that could reverse the oppressive aspects infused into ourselves.

Preparation for collage intervention, 2021

Sunita: Within the gestures in the video and the poem there is, to me, a feeling of tension between the meditative and the obsessive. The collage gestures, and the tweezing out the stones from the sand gestures. It could be read as meditative or obsessive, and I wondered if that's something that you were thinking about?

Emily Brandt: Yes. The whole book is like that. I think to meditate, you have to travel through the obsessive mind as well. And so I like the idea that meditation, as a goal, is very fraught. It’s a thing that happens and then it goes away, and then it happens and then it goes away, and we come back into the obsessive mind. We can make attempts, and we can fail and then succeed and then fail again.

I was raised Roman Catholic, and my mom is very deeply dedicated to a prayer practice. And so growing up, we said the rosary all the time, all the mysteries of the rosary. You go five times around the whole thing. It takes hours, you do it with all the women in the neighborhood, all her friends. It was always the women. The women would gather and they would pray together. And I would be there, probably stoned, Hail Mary-ing with the women, and had feelings about it often like, "Get me out of this Catholicism thing.”

Sunita: It does sound amazing at the same time, though.

Emily Brandt: Yes. It is. It took me a long time to understand, "Oh my God, they're witches. It's amazing.” For me, these prayer practices are absolutely both obsessive and meditative.

I think a lot about the image of the dancer, Margherita Tisato, that I'm manipulating in the video. I can't speak to her experience, but I understand some of her perspective from talking with her and reading what she writes about ropes and suspension, and I'm interested too, in these practices as a means of exploration, or some other kind of embodied undoing.

This idea of constricting the body and working through physical discomfort or pain as a way, not just to meditate, but as a way to undo some of the trauma and some of the assumptions and ideas that have been programmed into us.

Sunita: That’s beautiful. I want to switch gears from human bodies to plant bodies, because that is a running theme in your work. And it seems not just that you’re using nature and plants as metaphor, but more like a kind of inter-species dialogue.

Emily: One of the biggest revelations of my life was the moment of knowing that plants are smarter than animals, and feeling a huge curtain lifted.

Sunita: What was the moment?

Emily Brandt: Walking through the jungle in Costa Rica. There's some of the most amazing plants. There are walking trees, mangroves, that move towards the sun slowly over time. And brilliant ceiba trees, with lethal thorns. There are all these adaptations, and so many different poisonous plants, and obviously hallucinogenic plants as well. And we're very cut off from that. I mean people in the U.S. spend money and time blaring leaf blowers to keep leaves off of their lawns, like a leaf on the grass is some ungodly sin. One of the things that I grieve about assimilation in the United States is how people get cut off from the plant medicine of their ancestors.

Sunita: I have just one more question about being a poet in a video cooperative. My friend, poet and curator Ariel Goldberg, once said to me, "Poetry is the prime example of the least economically viable art form, especially if it's experimental. So it is a form of censorship in this country to make it as difficult as possible for a poet to produce a large body of work that is questioning information and creating new information." You seem to have managed to resist that censorship. You've put out this book this past year, you've created a large body of work that does this, but I wonder if we can talk a little about one of Temp. Files’s missions, which is to foster cooperative support for artists in a time of scarcity. Does the Temp. Files format work particularly well for a poet? Or particularly badly?

Emily: I love the collaborative approach. It's so nourishing to have a space, have a community to bring work to while it's gestating. And that happens a lot, but often in ways that feel colonialist and boring. So it's been nice to have something more open and nurturing, that is still very rigorous.

I like how Temp. Files is calling ourselves a residency. That’s challenged the way I think about the group. What if this isn't just a Zoom meeting where we're getting and giving feedback, but rather, what if we conceptualize this as a place where we reside? As a place we are living in that is nurturing us and our practices, the way a home might.

April 2021